An Unexpected Final Stop: The Eastern Trans-Siberian

- Aaron Schorr

- Apr 28, 2020

- 18 min read

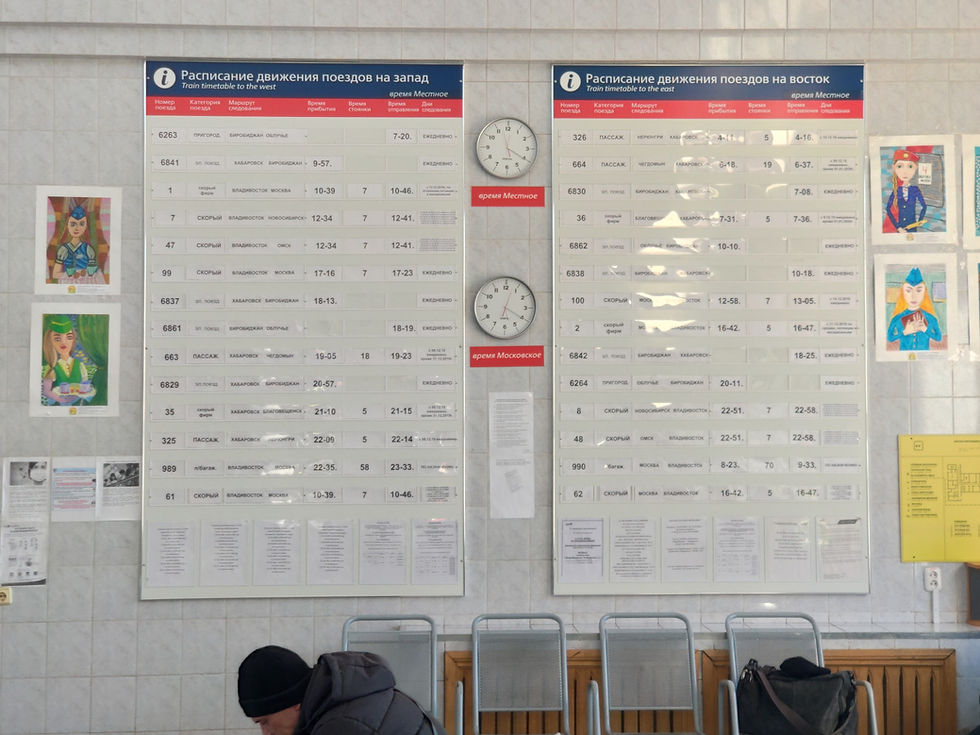

We left Svetlana and walked through the outskirts of Birobidzhan towards the bus that would take us to the train station. There was fresh snow everywhere, and a distant factory was belching smoke above the rows of brick housing blocks, just like it had been doing for decades. The station itself was mostly unchanged, too, with a paper timetable divided into east and west. We were boarding the same train we had gotten off the previous day, only this time our carriage was a Soviet-era one, with heavy leather seats and oppressive heating.

This leg was supposed to last just under 52 hours, taking us from Birobidzhan to Ulan-Ude, a city two timezones to the east between the Mongolian border and the eastern shore of Lake Baikal. This was the true Trans-Siberian, over two days of riding through nearly empty wilderness. We made our beds, got comfortable, and settled in for the long ride. We had the extraordinary luck of having the 4-bed kupe compartment to ourselves and hoped it would stay that way for as long as possible. 2 people in a kupe compartment was comfortable, 3 was tight, and 4 was downright claustrophobic.

Our daytime provotnitsa was Tatyana, who was even more matronly than the previous one, tut-tutting us if we got off the train without proper winter clothing and refusing to accept she couldn't just carry on a conversation in rapid-fire Russian with us. After boarding, she immediately gave us Russian Railways-branded mugs to make tea, which were a fixture of long-distance trains in Russia. The mugs have an elaborate metal base, emblazoned with a Russian eagle and the Cyrillic characters Р-Ж-Д (Российские Железные Дороги, Russian Railways), and a removable glass to facilitate cleaning on the train. I was smitten and later bought a Trans-Siberian-themed one for myself.

Time assumed a relative quality on board. I would look out the window, spend an hour reading, look out again and the scenery would seemingly remain unchanged - endless rolling hills covered with snow and taiga, the prehistoric Siberian forest. The time of day didn't matter, only the time remaining to the next major stop and to our destination. The train would make long stops of half an hour or longer several times a day, which were perfect for stretching our legs, getting some fresh air, and restocking on food.

Illicit Kiddush on the Trans-Siberian

The first such stop was in the town of Belogorsk, roughly 400 kilometers north-west of Birobidzhan. The entire town, which had a population of 65,000, was centered around the train station, its connection to the seemingly very distant outside world. The platform was lined with small shops and opposite the station was a large supermarket which seemed to be entirely geared towards rail passengers, selling mostly non-perishable goods and alcohol. It was Friday evening, so I figured we might as well get a bottle of wine and some bread and try and have a nice Friday night dinner.

I still had some spare time after the shopping trip, so I set off deeper into the town. It was -10° with a good six inches of snow on the sidewalks, which just added to the effect of being frozen in time. There were some boys cleaning the ice in a hockey rink, a sports bar named Sputnik, and a small fruit stand. A single block away from the station, the silence was total, with hardly a person in sight. Endless rows of ugly housing blocks lined the streets into the distance until the street lights ended.

Back on the train, Tatyana walked into our compartment, saw the bottles of wine and beer on the table, and shook her head disapprovingly. "We aren't allowed to drink here?" I asked.

"No, only in the restaurant."

"And where is the restaurant here?"

"V etom poezde - nyet." This train doesn't have one.

This was classic Russian logic - you can drink in the restaurant car, but it doesn't exist. It was like being back in the military. We realized we didn't have a corkscrew, so I ended up pouring the beer into my RZD mug, making Kiddush on it, and hiding it between my leg and the wall like a teenager hiding alcohol from his parents; the wine would have to wait for less hostile circumstances. After dinner, we dimmed the lights and opened the curtains to gaze at the clear night sky, pinpricked with millions of stars in the total absence of light pollution. I felt an eternity away from everything and totally at peace.

Siberian Mark Zuckerberg

The next day was a blur of food, scenery, and people, spent on the train from morning to night. I really wanted to get to know some of our fellow passengers better, especially the trio of young paratroopers two compartments down from us, but nobody seemed to speak any English and carrying on a conversation without simultaneous translation (impossible without cell reception) was too difficult.

The one person who did speak some English, and certainly seemed interested in getting to know us, was Zagit, the provotnik of one of the third-class carriages. Once he heard we were from Israel, he immediately dubbed me "Ashkenazi" and Yotam "Mark Zuckerberg", and attempted to list every Israeli sports figure he knew (which were quite a few). We both liked the basketball team CSKA Moscow, and hit it off right away. He was super kind to us, even gifting us RZD pens, and swapping army stories with us. Serving in the Israeli military was "great", according to him, since we had women and therefore it was "not boring". He, on the other hand, had spent a year guarding a forest in the Russian Army with no women around (and probably getting hazed by his superiors).

There were no cities on this stretch, nothing at all except endless taiga, snow, and dirty, forgotten towns. The towns were fascinating places, outposts of post-industrial decay with curious names like Takhtamigda, Shireken, and Yerofey Pavlovich. Whenever the train would stop for more than a few minutes, I would be ready by the door in full winter gear, waiting for the train to stop so I could have a few precious minutes to stretch my legs and explore another world. I was generally joined by most of the males of the car in need of a very cold cigarette break. Once out of the station, the streets were invariably silent, the towns seemingly slowly decomposing like dead organic matter, unimpeded by their impoverished residents. The collapse of the Soviet Union still reverberated loud and clear, with sooty abandoned factories serving as monuments to what passed for the glory days in this remote corner of modern civilization.

The train station was often the only decent building in town, clean and well-kept like the set of Dürrenmatt's The Visit. There was invariably a statue of Lenin standing watch over the rails, always with an outstretched hand or finger pointing forwards. The message was clear: Follow me to a better future! In the West, we tend to think about the Soviet Union as an evil empire that belongs in the past; in Russia, it's a nostalgic memory of past glory that lives on through its successors. Post-Soviet Russia is not post-Nazi Germany - Russians are not apologetic about their country's past and Soviet leaders are viewed as heroes to this day.

The Case of the Disappearing Vodka

The temperatures were the coldest yet, dropping all the way to -13° at sundown, but the air in the old train car was stifling. In an attempt to find comfort, we took to drinking hot tea in the passageway between cars, which was almost as cold as outside. We had a bottle of vodka, too, unintended contraband to pass the time, but it had become warm and undrinkable. In an attempt to cool it down, we hid it in an electrical cabinet in the same passageway together with a bottle of seltzer, but when we came back for them we found the cabinet suddenly locked. It was eventually unlocked a few hours later, but the bottles were nowhere to be found.

The landscape was boundless, beautiful in its cold, empty expansiveness, seemingly untouched by man. The hours spent gazing out the window left me in awe of the incredible accomplishment that the railroad was, carved out of the wilderness for thousands of miles in an era when most Russians were impoverished peasants playing a belated game of catch-up with their more western counterparts. To a Russian 100 years ago, being able to take the train from Moscow to the Pacific coast must have seemed even more novel than air travel is today.

The effects of this momentous project were plainly visible - Russia had expanded its borders into Siberia as early as the 16th century, but there had hardly been anything Russian beyond the Urals until the railroad connected Moscow to its vast hinterland. None of these towns had any existence without the railroad, the lifeline without which they would have ended up as decrepit of the towns of the Central Asian republics after the Soviet empire collapsed. The economic significance of the railroad was also clear - Putin's Russia is a petro-state, with oil, gas, and mining virtually the only sources of state income, and the railroad ensures these can be transported smoothly and by Russian hands from the mines and oil fields of Siberia to the homes and factories of China and Europe.

The railroad has assumed even more significance as the "Eurasian Land Bridge", part of China's "Belt and Road Initiative" (remember that from Mombasa?), in which it plays a major role in transporting Chinese goods to European markets faster than container ships can. China has established new direct freight rail links with London, Madrid, Leipzig, and other European cities, and all these trains must use the Trans-Siberian for part of the way. Cargo trains outnumber passenger ones by a significant margin, long snakes of oil tankers, coal hoppers, and boxcars stretching for kilometers in marshaling yards larger than the towns that host them. This is the single most important piece of infrastructure Russia has, so it's not surprising that the railroad remains in good condition when most Russian infrastructure is in decay.

The Noose Grows Tighter

Cell reception along the line was even spottier than I had expected, for the most part disappearing within two minutes of departing a station. When we had boarded in Birobidzhan, business was as usual in Russia, and we felt like we had beaten the pandemic for the time being. In the space of two days, however, the situation had deteriorated, with the number of COVID-19 cases across the country spiking and the land borders with Poland and Norway closing. Information came in at a trickle every time we passed through a town, and it kept getting worse.

Researching my other options, it seemed the entire world had spiraled out of control over the past 48 hours. Borders were closing at a whirlwind pace, and every option I considered became irrelevant within a few hours. Continuing to Central Asia as planned had already ceased to be a realistic option, as most of those countries had closed their borders, but I had at least hoped to be able to remain in Russia for a while longer. The situation in Russia was clearly deteriorating, so I thought of going to Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary, but the EU announced its external borders would be closing to foreigners the following day. My next option was Turkey, but everything seemed to indicate it would be closing its borders in the coming days. Sitting in a Soviet train car and relying on snippets of information, it felt like World War II, a far cry from the world of easy, visa-free air travel I was accustomed to.

My parents were putting heavy pressure on me to leave Russia, and while I had initially dismissed them as alarmist, I began to see that they were probably right. It was Saturday, and Yotam and I decided to depart Russia by the end of the week. This meant that if we wanted to visit Lake Baikal while still leaving me a chance to complete the Trans-Siberian journey we would have to skip Ulan-Ude, so we simply booked a ticket on the same train onward to Irkutsk, which was the next major stop, albeit in a more modern car.

Mongols, Mountains, and Mischief

The 45-minute stop in Ulan-Ude was enough to grasp what a strange hybrid of a city it was. The architecture was a mix of Buddhist-influenced public buildings and Soviet brutalist, and most people seemed to be ethnically Mongolia or Central Asian, with few Slavic faces in sight. The station was enormous, ordinarily a major terminus for freight and passengers traveling between Russia, Mongolia, and China, but still full of activity despite the closed borders. We dashed out of the station and down Lenin Avenue to the "Monument to the Workers of the Locomotive Depot Fallen During the Great Patriotic War", which must be a one-of-a-kind place, even in such a monument-obsessed country. The temperature was hovering around freezing, and the sidewalks were drowning in thick, muddy slush. The station itself had little shops advertising Tovari Iz Mongolyy ("Goods from Mongolia"), but the border had been closed for the past few weeks and thus not much was being offered; I had to settle for a cheese-flavored ice cream.

The eight additional hours to Irkutsk were difficult, mostly since I had mentally been prepared since boarding the train to disembark that afternoon, and yet here I was, still riding over 51 hours later. It was a glorious day without a cloud in the sky, all the better to appreciate the scenery which had taken a major turn for the better. Roughly two hours after leaving Ulan-Ude, the railroad reached the eastern shore of Lake Baikal, the world's largest freshwater lake. After days of uninterrupted taiga, it was like entering a whole different world: to the right was the frozen lake, a huge expanse of white with the opposite shore just barely visible in the distance; to the left - the snow-capped Kodar Mountains. We traced the lake all the way to its south-western tip, by which point darkness had fallen.

Our new car was much more comfortable, with one additional passenger in our berth who was friendly enough. The real star of the car, though, was a four-year-old girl with huge blue eyes named Alyona who was traveling with her parents. She kept popping into our compartment to show off her toys - a police car, a giant rubber spider, and a stuffed cat which would repeat anything said to it - and would run back down the hall whenever one of her parents called out her name. She had the whole car entertained, but it seemed our compartment was her favorite, since our neighbor kept feeding her candy.

A Final Decision

We finally pulled into Irkutsk at 10:20 PM on Sunday - 14 minutes short of 60 hours after boarding; 2,751 kilometers and 2 time zones away from Birobidzhan. The most staggering part of it was that since leaving Vladivostok we hadn't even crossed half of the Trans-Siberian: Moscow was still almost 4,800 kilometers down the line. We took a tram into town (a proper Soviet-era tram, a rarity in modern-day Russia) and found our hostel. Somewhat surprisingly, it was a fully-fledged backpacker hostel, meaning the receptionist actually spoke English and could give us the name of a late-night steakhouse to get dinner.

The food was good, but I couldn't enjoy it with the bad news I was reading online. I had barely left my phone since arriving in Irkutsk, playing catch-up with the developments of the past few days in which everything had seemed to change. The pressure was becoming unbearable and I started legitimately fearing not being able to leave the country in time and having to endure a prolonged lockdown in Siberia. While that certainly appealed to my adventurous side, reading what had happened in other countries hit hard by COVID-19 made me fear a collapse of the Russian medical system and economy, which was already starting to suffer badly from the ongoing oil price rivalry between Russia and Saudi Arabia. With a heavy heart, I decided to play it safe and get a flight to New York in the next few days. It was Sunday night and there were decent flights on Tuesday and Thursday; I booked the Tuesday flight before I could give myself a chance to change my mind.

Booking the flight was sad but also relieving; I didn't have to worry about being trapped as long as the situation remained stable for the following 36 hours. With my departure fixed, I was determined to enjoy my remaining time as much as I could. Here fate stepped in, and as I called my parents to let them know about my change in plans a guy from the next table started talking to Yotam. The man's name was Igor, and he seemed to be in his late thirties or early forties. He was from Moscow but spoke perfect English with a distinct Irish brogue, a result of some Northern Irish roots as we later learned. He was obsessed with Jews and even spoke some Hebrew as a result of time spent on a kibbutz in northern Israel. I asked why, and the response was "my Jewish friends were going, so I figured I might as well go with them".

The mixture of Irish and Russian blood had predictable results, namely a spectacular capacity for alcohol. One Negroni followed another, while he insisted I try and match his pace; Yotam dropped out after two. I had just spent 60 hours on a train and was in no shape to compete, but not before he tried convincing me to move my flight up by a day so I could celebrate St. Patrick's Day with him and his friends. The flight was non-refundable (and besides, I doubted my liver could handle it), so we compromised that we would have an early celebration the following night and he insisted on paying for all our drinks.

Standing on the World's Largest Lake

After breakfast the following morning, we headed to the center of town in search of the avtovokzal, or bus terminal, to find a ride to the shores of Lake Baikal. The easiest access was at the town of Listvyanka, at the mouth of the Angara River which then flows through Irkutsk on its long way to the Arctic Ocean. We happened upon the bus going there almost by chance, since the station wasn't marked on any map. "Bus" is somewhat of a strong term; this was technically a marshrutka, the privately-operated cramped and hectic shared taxis which are ubiquitous all over the former Soviet Union. During my trip to Georgia and Abkhazia in 2018, I had learned that marshrutkas are generally cramped, stuffy, and loud, with fearless drivers blasting bad music and attempting to break public transport speed records. Seat belts are as foreign a concept as a schedule, and this marshrutka lived up to my expectations, though it was somewhat tamer than in Georgia.

We had really wanted to go snowmobiling on the frozen lake, but our arrival was earlier than planned and I had given up hope that we could make it happen on the same day. The lake was pretty incredible on its own, however, massive to the point it wasn't really comprehensible. The temperature was actually above freezing, meaning the ice was a little soft at the shore, but the center was covered in ice several meters thick and full of strange patterns of cracks beneath a layer of fresh snow.

We walked onto the ice and away from the town, which was virtually deserted. It was another bright, beautiful day, and the mountains at the opposite shore were clearly visible on the distant horizon. The serenity of the frozen lake was periodically interrupted by huge hydrofoils carrying domestic tourists onto the lake. In case one had any doubts this was Russia, the vehicles were almost all painted in camouflage with large Russian flags on their sides, drifting all over the ice in mad patterns before discharging their passengers onto the ice. It felt like a dashcam video.

Surprisingly, one of the tour operators actually answered my email saying we could go for a snowmobile ride that afternoon. This was by far the most expensive activity I had seen in Russia - our one-hour rental would set us back ₱3,200 ($44), with prices for a full-day tour going above $200. We had lunch at a Georgian restaurant in town and set off in search of the tour operator. They had given us the wrong coordinates, so we ended up trudging 45 minutes through muddy slush as the sun beat down on us until we found the place, which naturally was literally the last building in town. It was the first time I had been hot in weeks and I didn't miss the feeling.

The White Terror

We walked into a trailer and were handed balaclavas and motorcycle helmets. Outside, there were three huge snowmobiles waiting - one for the guide, who didn't bother to introduce himself, one for a middle-aged couple, and one for us. The guide briefly showed us how the throttle and brakes worked, and then we were off, Yotam riding on the pillion as I followed the guide through the forest. Despite being something of an adrenaline junkie, I had never ridden a snowmobile before and it was exhilarating. Twisting your way down a narrow snowy path on a quarter-ton howling beast as the forest flies past at 50+ km/h is a thrill like few others and I think the smile didn't leave my face the entire hour we were out, even when I missed a turn and had to figure out how to back out of the trees safely. We rode into the forest, stopped and changed places, after which I got a taste of what the passenger seat was like (hint: unbelievably bumpy). The warm temperatures meant we had to remain in the taiga, since the lake ice was deemed unsafe for snowmobiles, but it felt just as Russian.

The couple we were with gave us a lift back to the main road, sparing us the long, wet walk, and we settled down by the roadside for what we expected would be a very long wait for the marshrutka back to Irkutsk, which naturally had no posted schedule. Through some stroke of unbelievable luck, the third vehicle to pass us happened to be the marshrutka, appropriately driven by someone who clearly thought he was a rally champion. Back at the avtovokzal, we walked through the city market, which was about what you might expect from a Siberian city at the end of winter, with lots of unidentifiable vegetables and cheap Chinese goods.

The city was at its absolute worst, with positive temperatures for the first time in months, so the streets were filthy and submerged in sooty water, at places half a meter deep, and unpaved sidewalks were a muddy morass. Mind you, Irkutsk isn't much to look at under the best of circumstances, with more than its fair share of decrepit buildings. Anticipating needing hand sanitizer for our upcoming air travels, we visited half a dozen pharmacies until we found two small bottles for sale. Thankfully, Russian cities are never lacking in pharmacies, and signs with the word apteka can be found on practically every street corner.

Some Very Unlikely Travelers

We still had the bottle of wine we had bought for the train ride and neither of us wanted to risk flying with it in our backpacks. We still didn't have a corkscrew, though, but I managed to work some magic with a knife and get it open. After dinner at a nondescript Korean place which was about as Korean as a parody of "Gangnam Style" we headed to a Belgian pub to meet up with Igor. He had warned us from making meeting too late since he had a "slight fear" he would be "totally smashed", but he seemed remarkably sober, chatting with a local friend named Vova, who was a man of few words but clearly enjoyed Igor's humor as much as we did.

We left the pub for a classier bar Vova recommended. Walking down the main drag (Karl Marx Avenue, naturally), I heard some American voices. I didn't pay any attention, until I remembered I was in Irkutsk and Americans were about as rare as clean cars. I turned to see who it was and saw four guys in their late teens, nicely dressed in collared shirts and sweaters. No way, I thought to myself, you aren't that drunk. Incredibly, my suspicions were confirmed and they were actually Mormons on their post-high-school missions - two Americans, a Brit, and an Austrian - in Irkutsk, Siberia. None of them had expected to end up here, but they were all very grateful they were (not that I had expected anything else) and were sad to be leaving the country prematurely because of the virus. If even the Mormons were leaving, I thought, we were making the smart move.

The bar was empty but great, with a pleasant library decor and the first really good cocktails I had had in a long time. And there were a lot of them, with Igor insisting I try this local specialty and that drink they make well, though he never departed from his Negronis. I was planning on staying up as late as possible to beat the upcoming jetlag, so my resistance was minimal.

Walking back to the hostel, we stopped at a 24-hour supermarket to buy snacks for the plane. I suddenly heard the last thing I expected to hear in a Siberian supermarket after midnight: Hebrew. A middle-aged Israeli woman and her daughter were doing some late-night grocery shopping, but they didn't seem nearly as surprised as us to see other Israelis. It was almost too much for me to handle.

The Longest Day

I was up just before dawn to catch the bus to the airport. I bode Yotam a very sad goodbye and walked to the bus stop. The airport was bizzare, two dark terminals seemingly plopped in the middle of a residential neighborhood with no signs, separated from the actual runways by crumbling tarmac. I had spent over 75 hours riding west on the train from Vladivostok, but Moscow was still a six hour flight in the same direction, which was real food for thought about just how enormous Russia is.

Sheremetyevo Airport in Moscow was eerily empty, vastly different from what it had been two months earlier when I had changed planes in it on my way to Vietnam. For the first time, I was actually worried about getting sick, sitting on a trans-Atlantic flight with several hundred strangers from all over. Fate wasn't done toying with me, though, and I found myself seated among a group of American Jewish seminary girls on their way back home to the US after Israel prepared to go into lockdown. I sanitized my seat and surroundings and kept myself occupied with reading and movies to avoid falling asleep until landing.

JFK was even more disturbingly empty, but even more disturbing was the ease with which I was allowed to enter the US. We were handed health questionnaires to fill out before arrival, but nobody asked me to actually hand mine in at the airport. The CBP officer asked if my temperature had been taken at the gate and seemed surprised that it hadn't, but waved me in nonetheless. I got my bag and exited the terminal, where my aunt Dina was waiting for me in a rental car.

Driving through New York City on empty highways was perhaps the most surreal experience of this very strange trip, and I couldn't quite believe I wasn't dreaming. As if to make it even more dream-like, it had quite literally been the longest day of my life. Leaving the hostel in Irkutsk, the sun came up and didn't set again until I was riding through Queens, over 25 uninterrupted hours later, after following me across Siberia, Europe, and the Northern Atlantic. This chapter had come to an unexpected end, but it had happened so suddenly that I hadn't had the time to process it, and thus I found myself in Dina's Manhattan apartment, wondering what would come next. What a time to be traveling and what a time to be alive.

Comments