Mumbai II: Colonial Clubs, Street Idolatry, and Environmental Catastrophe

- Aaron Schorr

- May 18, 2022

- 7 min read

Pradz finally arrived from the US, and we drove up the hill to visit his grandparents the next morning. In an apartment full of beautiful Indian art and a cupboard lined with alcohol miniatures from the past six decades, we sipped on nimbu pani (Indian lemonade) and had coconut sweets called ladoo. The 89-year-old grandfather had lived in Mumbai nearly his whole life, and was clearly a man of habit. Since 1954, he had gone to the same café every day for his morning coffee until it shut down during the pandemic. The grandmother was a native of Goa, and the generational divide between her and her daughter Prati was clear. She was dressed in a beautiful pink-and-red sari with a bright red bindi on her forehead, an outfit Prati told me she herself donned twice a year for special occasions. The neighborhood they lived in looked rather like Tel Aviv, with narrow streets flanked by palm trees and tall white apartment buildings with big windows.

It was Sunday, and Pradz’s parents wanted us to have lunch with them at the Royal Willingdon Sports Club. The club was founded by the governor of Bombay in 1918 after his Indian guest was refused entry to the white-only clubs in the city. Membership has been closed since 1985, and it is considered the most exclusive club in the country. We drove in past a lush 18-hole golf course, a swimming pool, and indoor tennis, squash, and badminton courts to sit on a beautiful white veranda overlooking one of the holes. I felt like I was in one of the opening scenes of Lawrence of Arabia. The club’s revenue comes from steep membership fees, so the menu prices rival street food, and the menu itself retains its English origins, with plenty of local fare, too. We had some egg and chicken sandwiches, served on white bread with the crusts cut off in proper London fashion. Later came some delicious Mumbai chaat (street food) – sev puri (unleavened bread with potatoes, tamarind, and tamarind chutney) and dahi puri (the same base with mung dal and yogurt). Unfortunately, they don't allow photos.

A Colonial Past and Nationalist Present

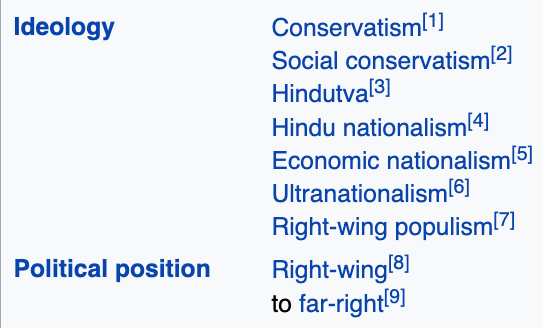

We drove down Marine Drive towards the old colonial center we had seen the previous night. On the way, Pradz explained to me the meaning of the orange flags I kept seeing on electrical poles and flown from taxis – they represented Shiv Sena, a far-right party that has

blended Marathi nativism with Hindu nationalism to rise to power in the state, at times through an uneasy alliance with the ruling BJP. Unsurprisingly, they were the ones behind the renaming of nearly all the city’s monuments after Shivaji, both a Marathi and a Hindu hero. A brief glance on Wikipedia shows you all you need to know:

In the old center of the city, called Fort, the streets are lined with beautiful old colonial buildings in various states of repair, and filled with vendors selling everything from sunglasses to sugar cane juice and 100 rupee ($1.3) books. As always, a mixture of dust, smog, and diesel fumes fills the air with a constant soundtrack of honking. We walked around and ducked into some spectacular stores, including one selling upscale traditional Indian dress – kurtas, dupattas, and saris – in the most eye-watering colors.

One of the most beautiful (and cleanest) buildings was the synagogue, which was unfortunately closed on Sundays. We visited an art gallery displaying tribal art, took an obligatory photo on the steps of the Asiatic Society, and tried hiding from the heat in the beautiful Horniman Circle. The rest of the buildings are mostly bank offices, but everything in the area seems to be owned or sponsored by the Tata Group, the gargantuan Indian conglomerate that owns or produces everything from Air India to cars, chemicals, and consultants. A sign showed that they had also renovated the park, and owned the Starbucks across the street to which we eventually fled in search of air conditioning. Unsurprisingly, a chai latte in Indian Starbucks tastes exactly the same as the American version.

We returned home and joined Pradz’s parents on a walk in the nearby seaside park. On a Sunday evening, the park was full of families, but we headed to a fenced-off track around a soccer pitch, which was open to paid members only. In the US, exclusion from facilities and amenities often relies on mere geographic distance, but in a city as dense as Mumbai, class segregation assumes much more explicit forms.

The grandparents joined us for dinner again, which was followed by kulfi (Indian ice cream) and paan, snacks based on betel nuts eaten to improve digestion. My favorite was the Calcutta paan, which had menthol and rose petals. When we were done, we joined Ajoba pacing the length of the house. This was a shatapawali, Marathi for “hundred steps”, a traditional stroll after a meal which he swore was behind his good health at nearly 90.

We set off across the city the next morning to Gol Deval, a Hindu temple located on an island in a busy road. The scene was full-blown commotion, with worshippers on their way in and out of the temple attempting to cross streets thronged with taxis and carts as a man washed two cows that were tied up at the end of the island. Inside, visitors rung a bell to announce their entry and exit to the gods, offered their prayers, and made offerings at an inner shrine occupied by a bald priest pouring milk at the feet of a statue of Ganesha, a particularly beloved Hindu god. The scene was properly biblical in its idolatry, and all eyes were on us throughout.

Further down the road is Chor Bazaar (Thieves’ Market), which Bilal claims was actually mistranslated by the British and should be Shor Bazaar (Noisy Market). It sure was noisy, with rows of narrow stalls specializing in goods from power tools and electrical outlets to safes and antiques. The main drag was devoted to cars and motorbikes, and was most impressive of all. We passed workshops with men tinkering with entire rows of engines, transmissions, and brake discs, and even two men hammering away at an entire Fiat hatchback, taking it apart piece by piece. With their constant honking, Mumbai drivers evidently needed to replace their horns with some frequency, as we passed no fewer than three stalls exclusively selling and repairing them, producing loud honks at point-blank distance with no warning. As seemed to be the case with much of the city, the bazaar was religiously homogenous, and every shopkeeper’s name was visibly Muslim.

A friend of Prati’s had insisted on making us lunch, and sent over two steaming stacks of aloo paratha, pancakes made of whole-wheat flour and stuffed with potatoes, spices, and ghee. The pancakes were then dipped in spicy pickled carrots and mangoes and topped with homemade yogurt. I thought it was rather like an Indian version of latkes – that is, phenomenal.

My weather app was showing a heat index of 45º and our jet-lag decided to make an appearance, so after a nap we set off to Colaba Causeway, a major shopping street downtown. Prati and Pradz were much more adept at navigating the crowds than Richard or me, but we eventually all made it to our destination – Café Leopold, owned by Mumbai Iranis since 1871. The Iranis are a distinct group of Persian immigrants to India around the turn of the 20th century, and a sign on the wall stressed that they were different from Parsis, who are a prominent Zoroastrian community in town. The place was what I’d expect a hybrid of a British colonial cafe in the 1930s (think Tel Aviv) and an American dive bar to look like, but the chicken tikka was the juiciest I’ve ever tasted and the beer was cold. The café had been a target of the 2008 Lashkar-e-Taiba terrorist attack in the city, and the walls, ceiling, and pillars still bore large bullet holes – in fact, I almost tripped over one in the floor.

Speaking of Parsis, we walked around the block to Cusrow Baug, one of five Zoroastrian gated communities in the city, where two friends of Prati showed us around. The place basically looked like a Florida suburb, but the break from the constant honking was more than welcome. the various baugs are essentially self-sustained communities, built around a fire temple with sports facilities, a clinic, and a clubhouse in which older members learning to dance were visible.

A Shiva for Everyone

We returned to the Gateway to India with Prati the next morning, but headed to the bustling ferry dock behind the arch. After much commotion and what I can only describe as a game of bumper boats, we finally left the choppy harbor waters and made for the bay to Mumbai’s east. What made this delicate maneuvering even more impressive was the fact that the captain on the upper deck had nothing but a wheel and a bell, with which he wonld signal throttle settings to another man on the main deck. It was like watching an ocean liner from the 1930s.

I had spent a fair bit of time this past semester learning about environmental catastrophes, and the Mumbai harbor embodied several simultaneously. Sitting under a blazing sun with suffocating humidity, you peer through the thick layer of smog to view a swarm of oil platforms, tankers, and terminals, with the smokestacks of a distant refinery barely visible at a distance of 2 miles. Closer by, the cranes on a coal hauler dumped their black cargo into barges bobbing on the cloudy brown water. Despite this apocalyptic view, our arrival dock had rather hopeful environmental murals painted on it.

Our destination was Gharapuri Island in the bay. We met our guide Avinash and he escorted us onto a zoo-style train with “natural air conditioning” – that is, no windows or doors. On the island proper, we climbed up several hundred stone steps to reach the entrance to the Elephanta cave complex, where Richard and I were promptly charged 15x the admission price as our Indian host. One woman was having a much easier time, carried up the mountain in a litter by four men.

The caves were dug into the basalt mountain over 220 years culminating in the 6th century and are an astounding architectural achievement. Twenty-six intricate pillars hold up the high ceilings which used to be brightly painted but eroded in the salty air, and the walls are covered with intricate three-dimensional carvings of various forms of the Hindu god Shiva, generally accompanied by many other gods and goddesses. Many of the monuments were defaced and damaged first by India’s Muslim rulers and then by the Portuguese who colonized Bombay in the 16th century and used the caves for target practice. Some of them still even have visible bullet holes and Latin characters engraved into them, but others were restored over the past 50 years. The most impressive piece is a statue standing 25 feet tall and depicting the three aspects of the Hindu gods, which conveniently map onto the acronym GOD: Generator, represented by Brahma, Operator, represented by Vishnu, and Destroyer, represented by Shiva.

Comments